SECESSION . 202.11.1991 – 05.01.1992 . Wien

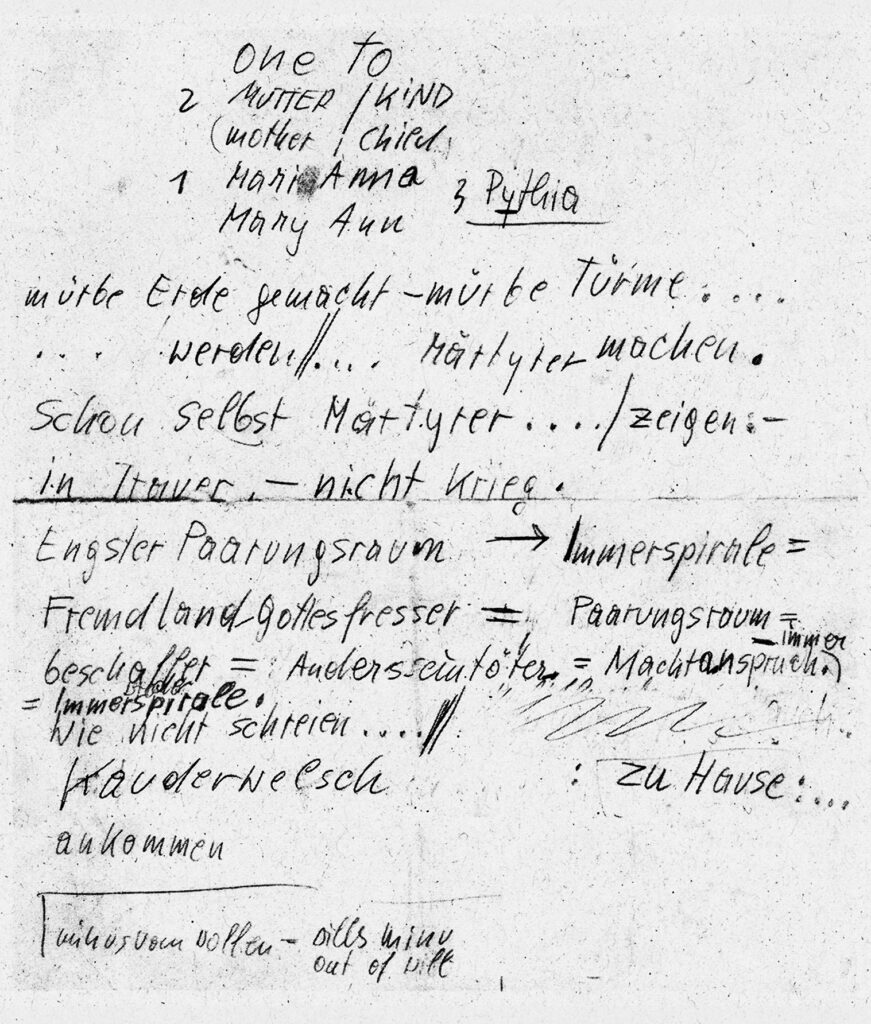

MM: War dies meine Prognose? – Nine-Eleven: 11. September 2001. _______________________________________________________________________________

MM: Was this my prediction? …-Nine-Eleven: 11. September 2001. _______________________________________________________________________________

Marianne Maderna: RAUM und AUSGANG . Texte: Hildegund Amanshauser, Jaques Derrida, Ulli Moser, M.Maderna. Foto: Margherita Spiluttini, M.Maderna . Secession, Wien. 1991. ISBN 3-900803-45-5

The Corner of the Space – the Edge of the Block. Turning the Body-Space inside out.

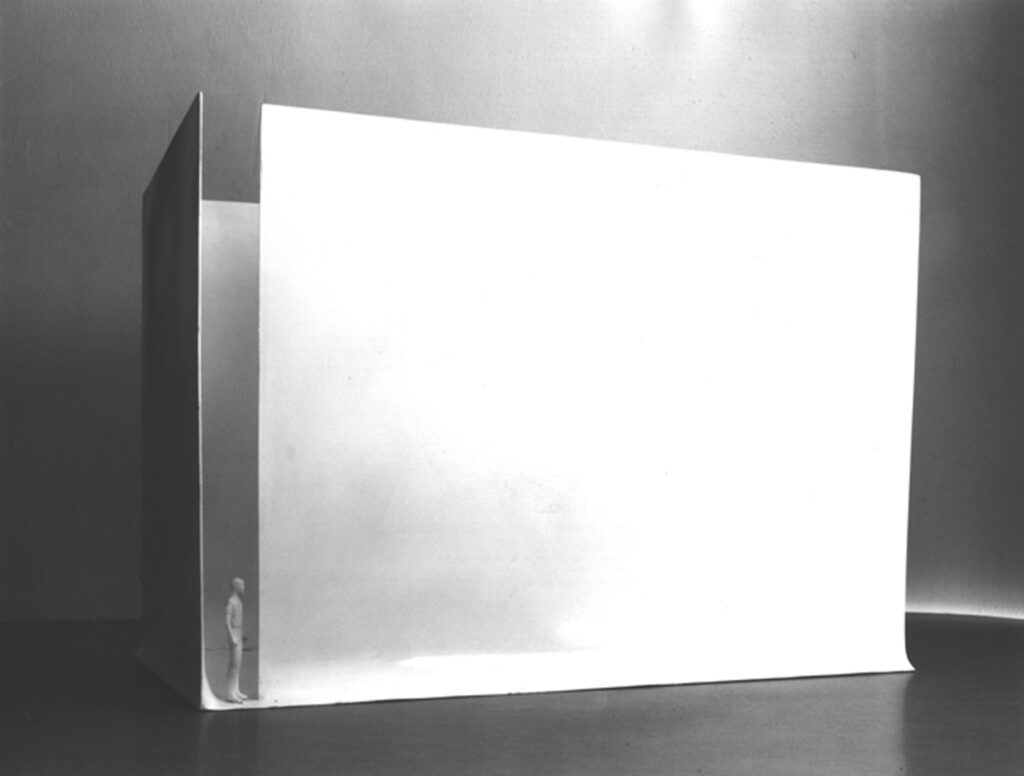

“….. – Anthropomorphisieren. Umstülpung – Körpervolumen – Hohlvolumen. Die Welt als “somatischer Kosmos”. – Hier als zweite Haut, oder semitransparente Wand-Öffnung. Raum-collagierte-Reliefs – und die begehbare Skulptur „Bau”. Ein Raum im Raum…..”

„…Das des “Umstülpens”, ist in besonderer Weise in der weiblichen Ästhetik zu verfolgen. – Bewohnen und bewohnt werden, Leibgehäuse und Körpervolumen, – Gefäß und Skulptur…“. Siehe Armin Wildermut: „Body-Awareness-Painting” von Maria Lassnig. ________________________________________________________________________________

“…..Seeing with your hands – anthropomorphizing. Eversion – body volume – hollow volume. The world as a “somatic cosmos”. – Here as a second skin, or semi-transparent wall opening. Space-collaged reliefs – and the walk-in sculpture “Bau”. A room within a room……”

“…..The idea of “turning things inside out” can be seen in a particular way in female aesthetics. – Inhabiting and being inhabited, body shell and body volume, – vessel and sculpture…”. See Armin Wildermut: “Body Awareness Painting” by Maria Lassnig. ……” ________________________________________________________________________________

BauArt/Raumdenken/Markus Brüderlin:

Kommentar zum Hintergrund . Skulpturen von Marianne Maderna . 1996.

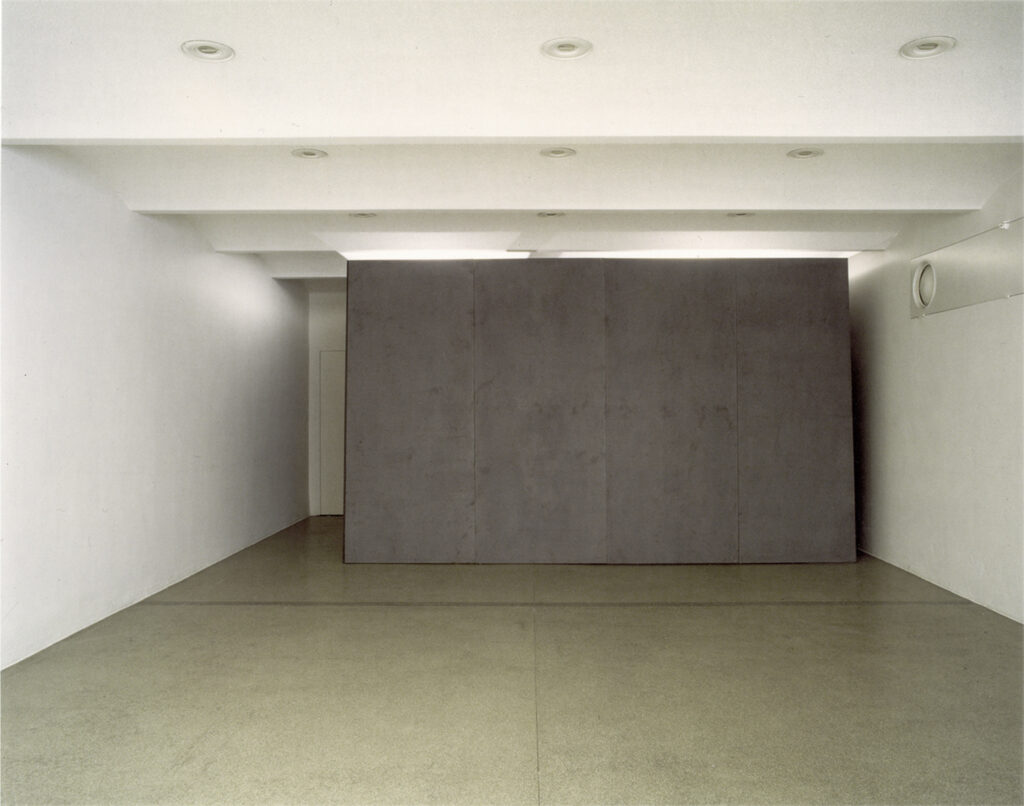

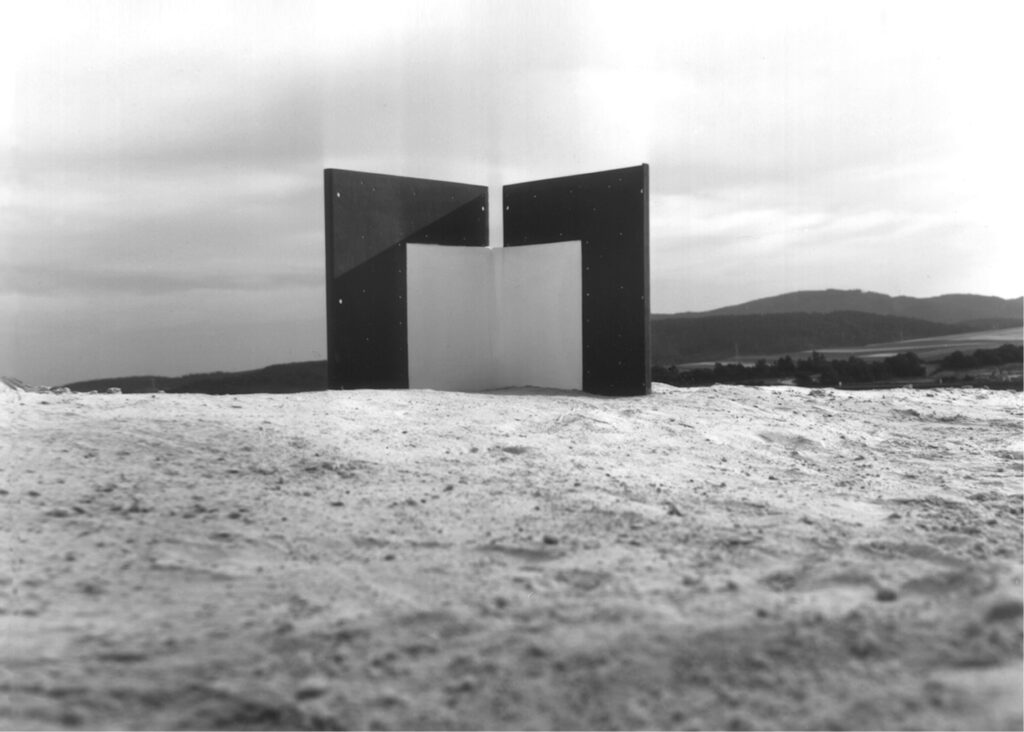

Dilatationssymmetrischer-Kunst-An-Bau. Dilatationssymmetrie = Selbstähnlichkeit (Fraktal): BAU: „.….Hier thront der Mastaba-artige Bau vor einer Insel. Eine raum – und zeitlose Toteninsel vor den beiden markanten Zwillingstürmen des New York World-Trade-Centers…..“ M. Brüderlin 1996.

_________________________________________________________

BauArt/Raumdenken/Markus Brüderlin:

A Comentary on the background: Sculptures of Marianne Maderna . 1996.

Dilatationssymmetrical art building: (photo) BAU: “…Here the mastaba-like building placed in front of an island. A space- and timeless island of the dead in front of the two striking twin towers of the New York World-Trade Centers…”. M. Brüderlin 1996 . MM: Was this my prediction? …-Nine-Eleven: 11. September 2001.

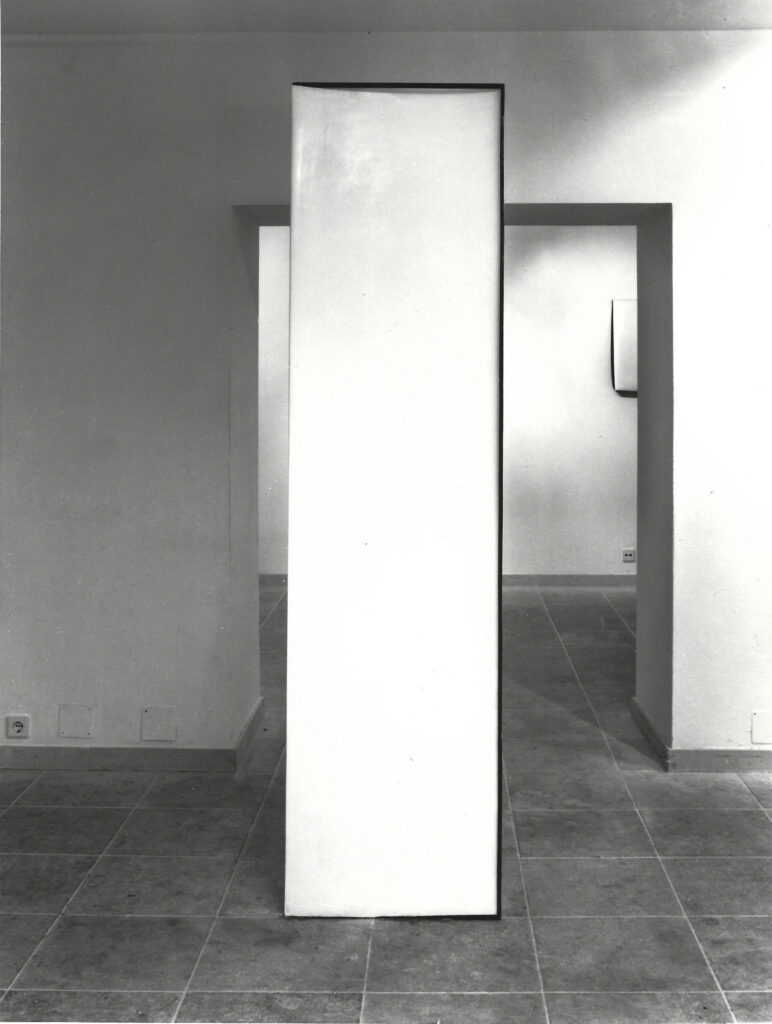

BAU . Eternit, Stahl . Wiener Secession 1991 . Foto: Margherita Spiluttini

BAU vor dem World Trace Center . Dilatationssymmetrischer-Kunst-An-Bau . Foto: Marianne Maderna . RAUM und AUSGANG .Wiener Secession 1991

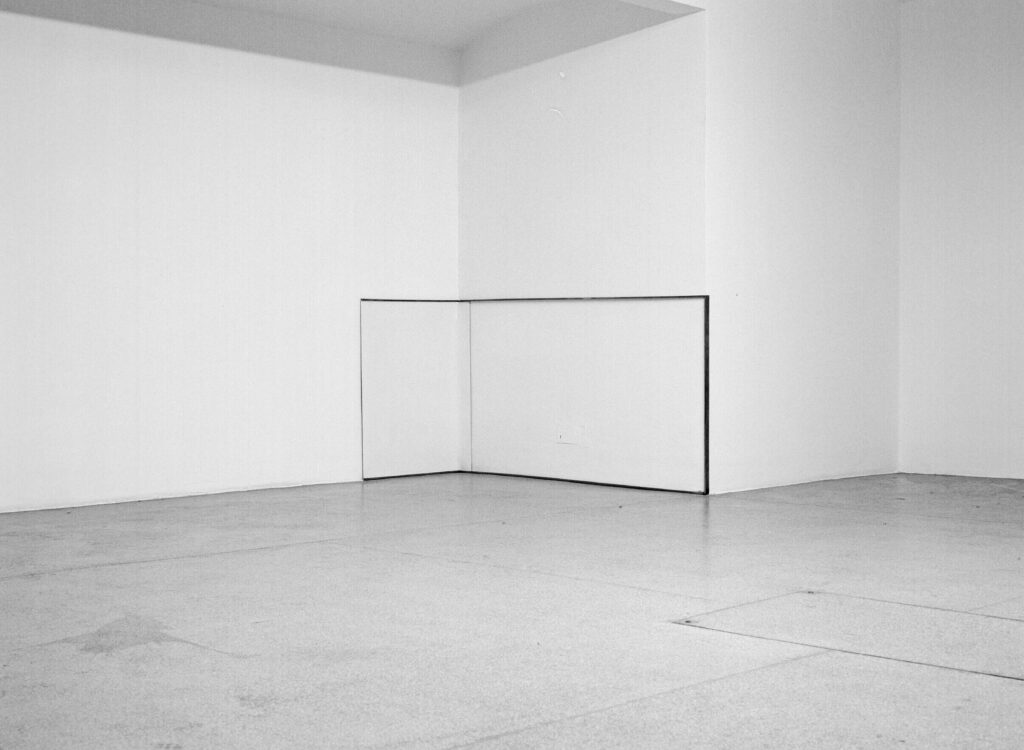

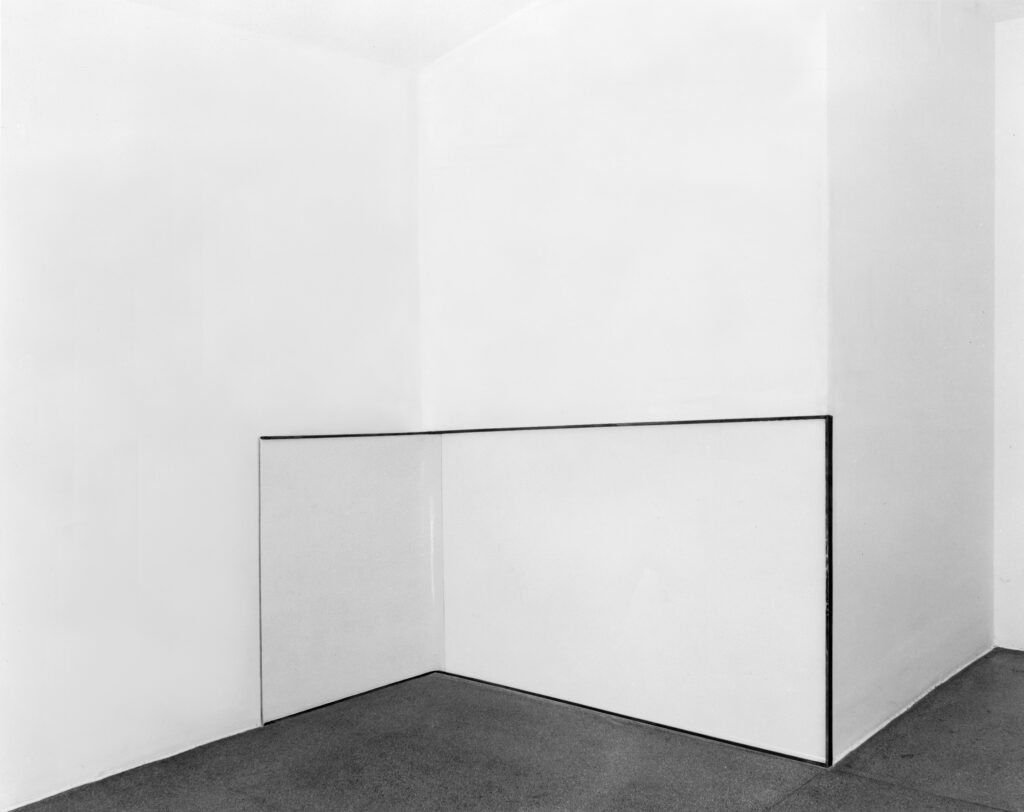

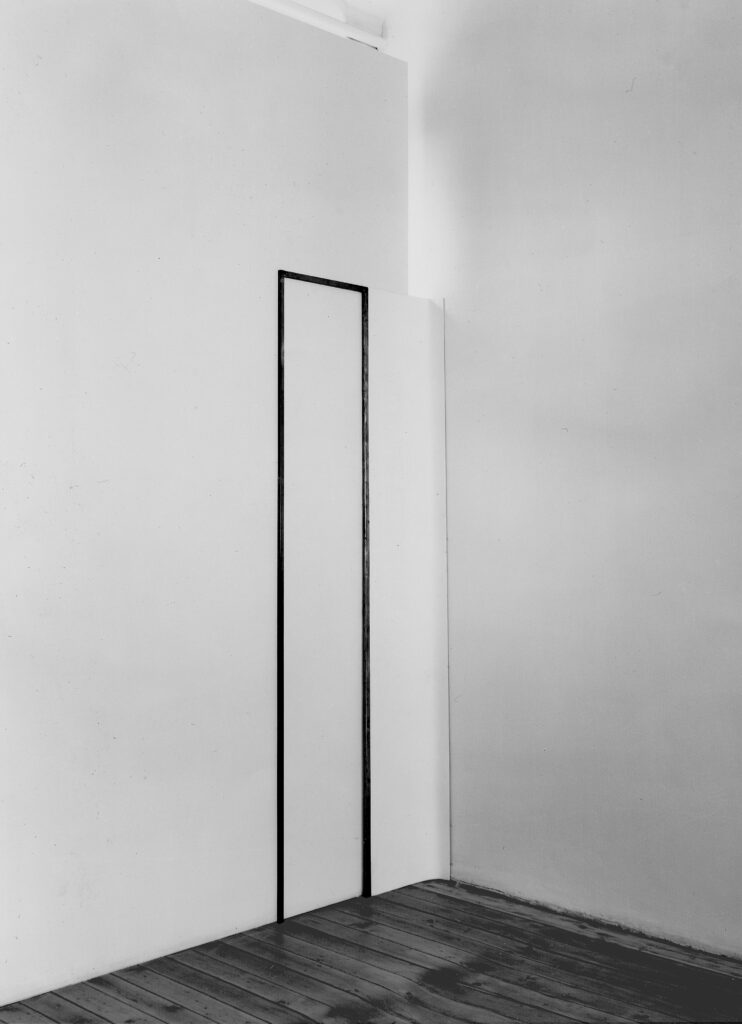

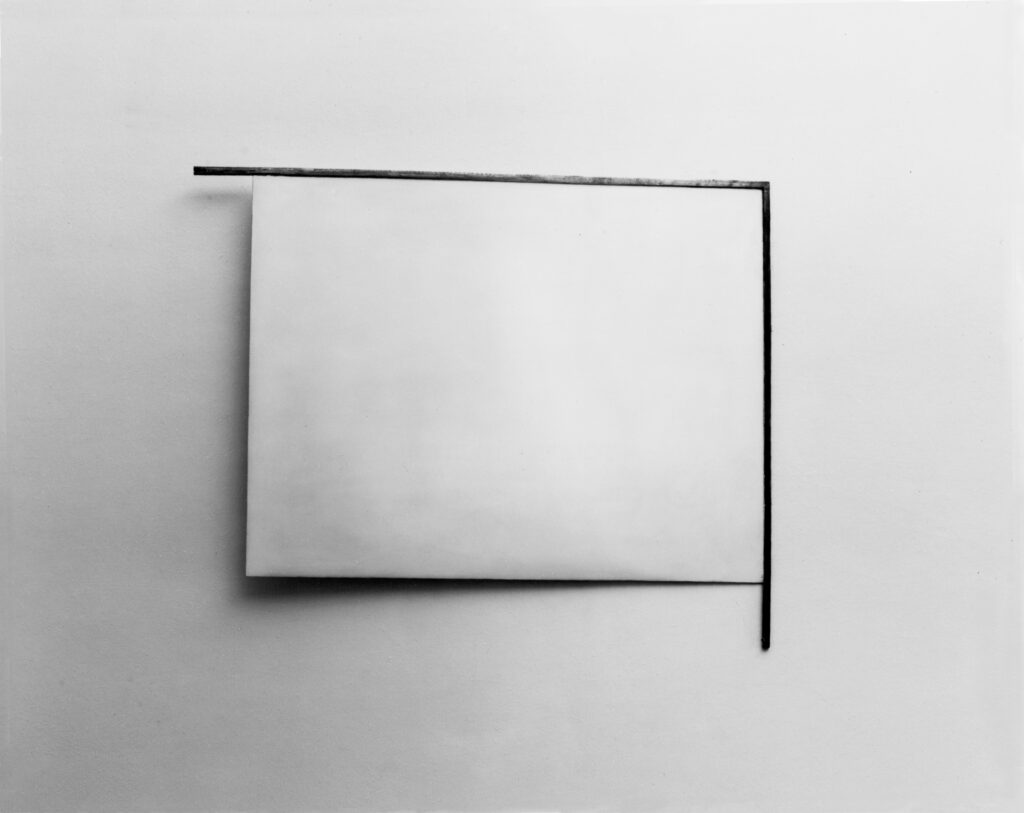

FENSTER . Spachtelmasse,Stahl,weißer lack . Wiener Secession 1991 . Foto: Margherita Spiluttini

MM: Mit den Händen sehen sagen die Blinden

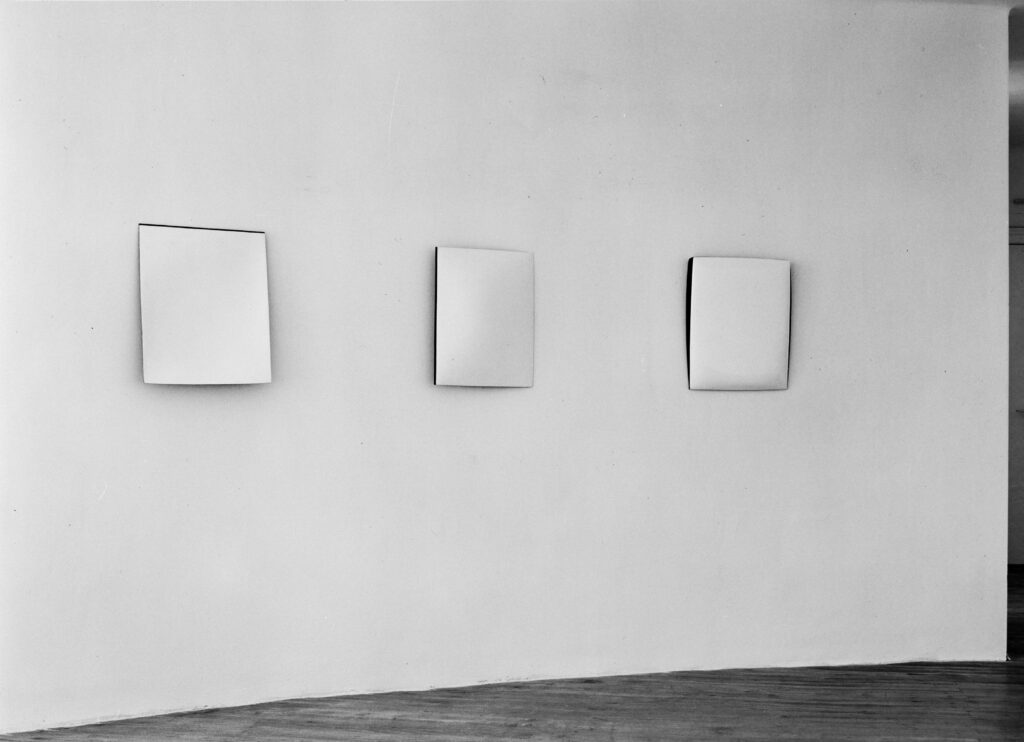

FENSTER . Spachtelmasse,Stahl,weißer lack .Wiener Secession 1991 . Foto: Margherita Spiluttini

FENSTER . Spachtelmasse,Stahl,weißer lack . Wiener Secession 1991 . Foto: Margherita Spiluttini

TÜRE . Spachtelmasse,Stahl, Graphit- lack . Wiener Secession 1991 . Foto: Margherita Spiluttini ——————————————————————————————————————–

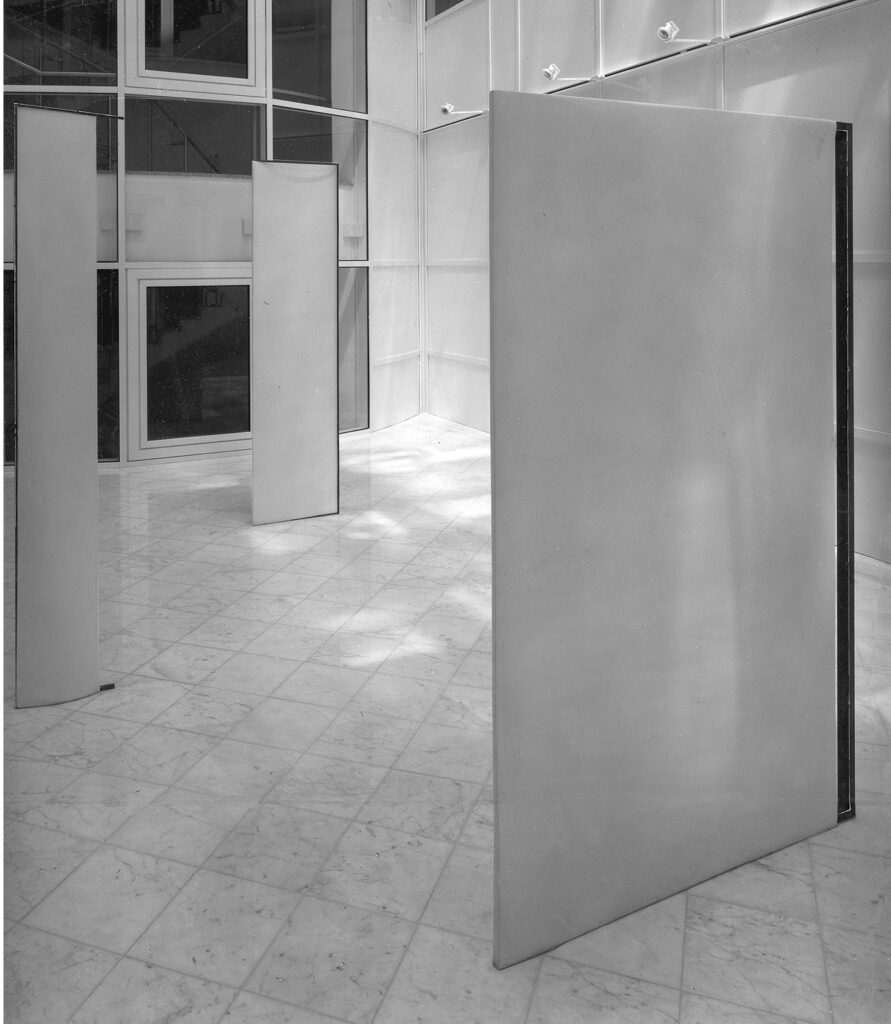

LOST HOUSE . Spachtelmassen, weißer Lack . Sammlung der Wiener Secession 1992 Foto: Margherita Spiluttini

MM: Das lange Leben der Menschen die in einem Raum gelebt haben wird auf den Tonträger-Wänden aufgezeichnet. – Hier als ein nach oben offenes weißes Raummodell. Die Ecken des Innenraums sind gegen den Uhrzeigersinn mit unterschiedlichen Materialstärken anthropomorphisiert. Die Höhen wechseln. Dadurch werden alle Maße relativiert. Der Baukörper scheint bewegt. Für den darin stehenden Menschen entsteht ein Umspringbild, ein Wechselspiel zwischen An – und Abwesenheit, – zwischen Täuschung und Realität, unmittelbarer Nähe und Unendlichkeit, wobei die Erfahrung außerhalb des Sehens liegt. – Die wirkliche Gestalt und Dimension des Raumes ist nur durch die Hand und deren Tastsinn zu „sehen“, – wahrnehmbar. ________________________________________________________________________________

MM: The life of the people who lived a long time in a room is inscribed on the recording-walls. – Here as a white room model that is open at the top. The corners of the interior are anthropomorphized in a counterclockwise direction with different material thicknesses. The heights change. This puts all dimensions into perspective. The building appears to be moving. For the person standing in it, a shifting image is created, an interplay between presence and absence, between illusion and reality, immediate proximity and infinity, whereby the experience lies outside of seeing. – The real shape and dimension of space can only be seen and perceived through the hand and its sense of touch.

TOR . Spachtelmasse, Stahl, weißer Lack . Foto: MM

BILD . Spachtelmasse ,Stahl, weißer Lack. Galerie Klocker . Sammlung Landesgalerie NÖ. Foto: MM

RAUMWINKEL – KÖRPERKANTEN . Spachtelmasse ,Stahl, weißer Lack. Galerie Menotti . Foto: Margherita Spiluttini

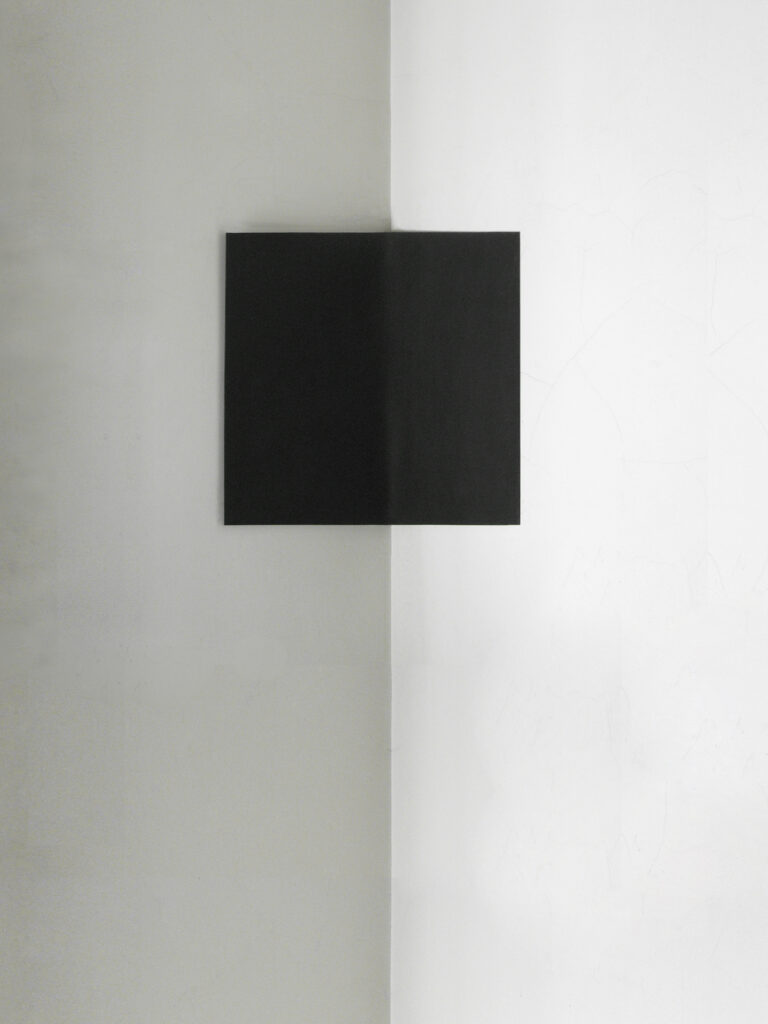

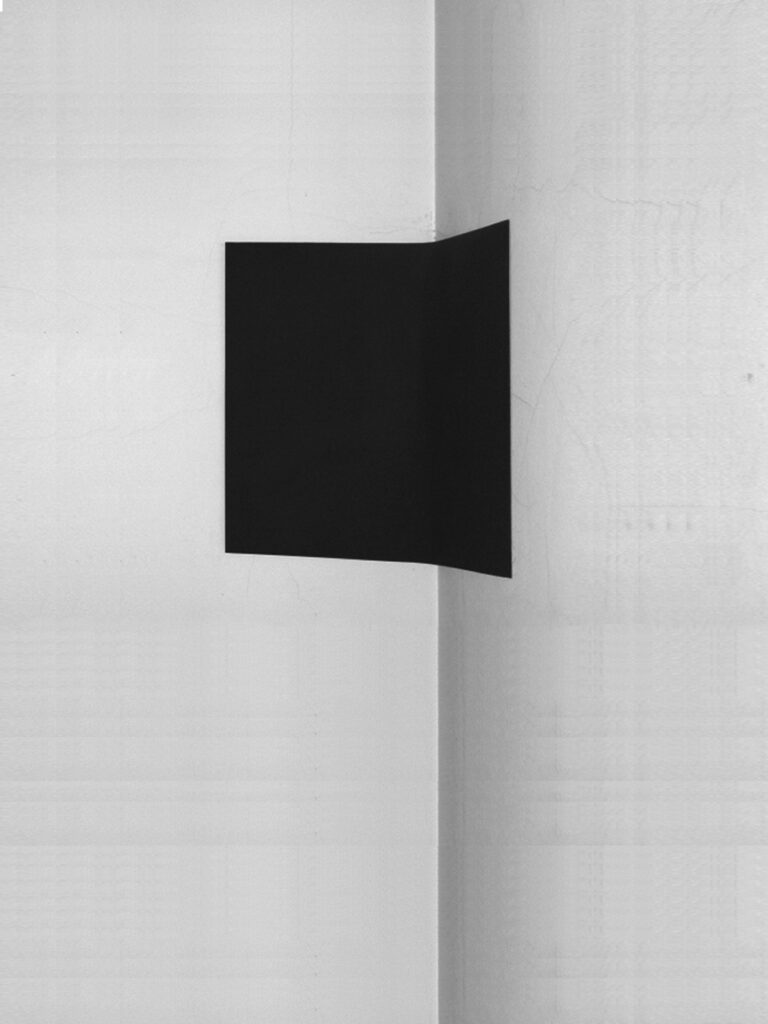

SCHWARZES QUADRAT . Spachtelmasse, Stahl, schwarzer Lack . Foto: MM

SCHWARZES QUADRAT . Spachtelmasse, Stahl, schwarzer Lack . Foto: MM